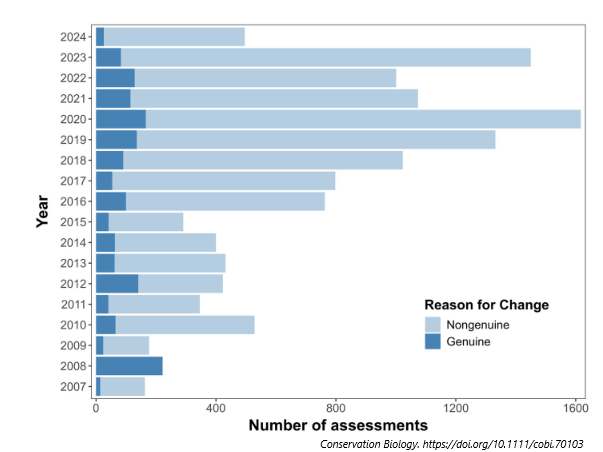

Despite the increasing number of species assessed for extinction risk by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (163,040 species as of 2024), only about 1 in 1,000 have been downlisted due to genuine population improvement. Although this rare conservation achievement has been widely celebrated in several recent cases, some other downlisting decisions have met with controversy. A primary role of the IUCN is to assess extinction risk. In this role, it must maintain its independence and not be influenced by the public outcry that may occur when a high-profile species is downlisted, even if well-established conservation programs may be disrupted or abandoned as a result. We explored the potential positive and negative consequences of downlisting for conservation efforts through case studies of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis), saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica), and black-faced spoonbill (Platalea minor), which has recently been proposed for downlisting. Although downlisting can enable more effective use of limited resources, these cases highlight potential risks, including weakened legal backing, diversion of resources away from the species, and declining public and political support. The relatively unquestioned downlisting of the saiga antelope illustrates how early and inclusive engagement of local experts, assessors, donors, and other stakeholders can help ensure that decisions are effectively communicated and implemented without jeopardizing species recovery. The IUCN Green Status of Species assessment is a complementary tool to the IUCN Red List and offers a useful measure of conservation progress, which can help decision makers ensure that downlisting does not undermine long-term conservation efforts.