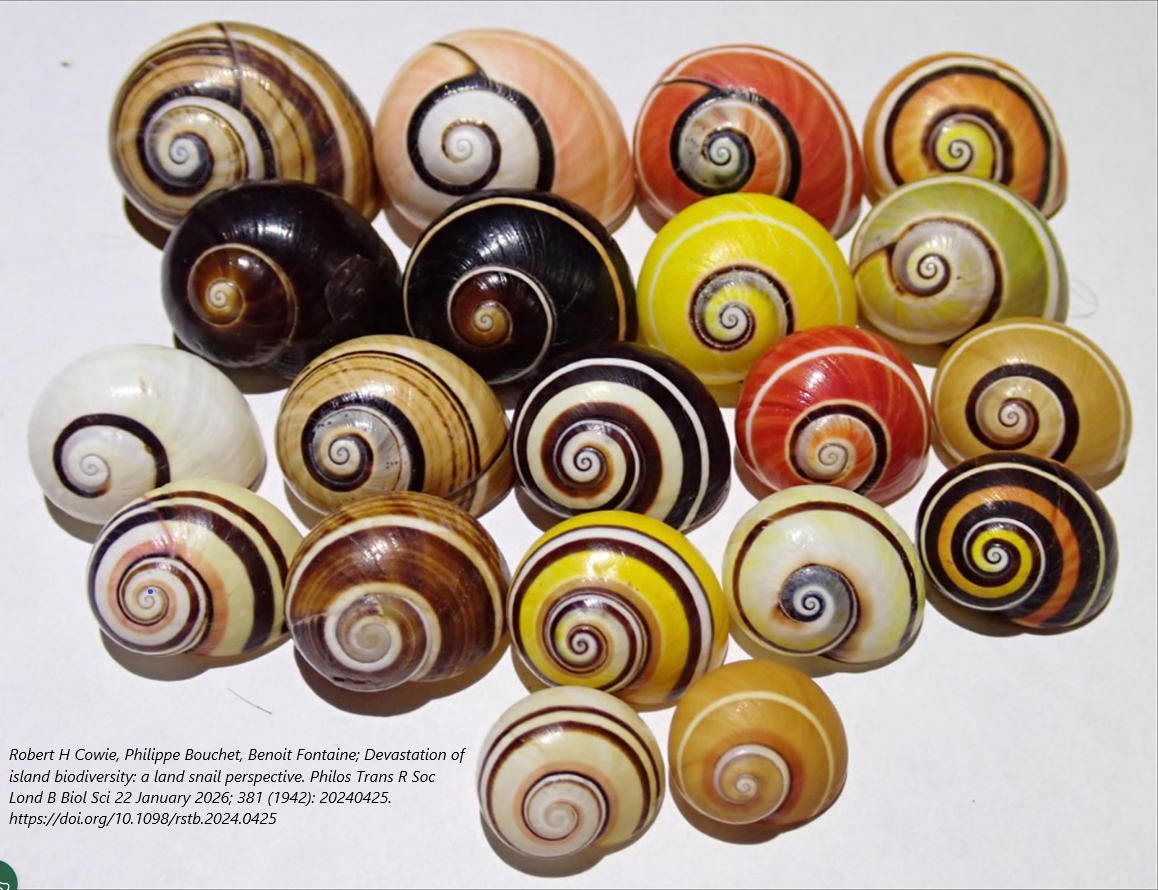

Many islands are remote and the level of interest in land snails as a component of the global biodiversity conservation agenda is low. The conservation status of many island land snail faunas thus remains at best out of date. However, land snails have an asset that other groups do not—their shells, which can remain post mortem in the shell bank of the soil for many tens or several hundreds of years after the death of the animal. Consequently, numerous island land snails are known only based on empty shells—modern but of uncertain age, and thus escaping the strict requirements for Red Listing extinctions after ad 1500. Many high volcanic islands had extraordinarily diverse and highly endemic land snail faunas, with 50–100 endemic species on land masses sometimes as small as 30–50 km2. ‘Devastation’ is not a hyperbolic term to describe the fate of many of these island microcosms, with levels of extinction variously documented but not uncommonly in the order of 30–50%, and up to 80%. Historically, loss of habitat—namely deforestation—has been the prime cause of species loss, triggered or accelerated by the introduction of livestock and other feral mammals, which did not directly impact the snails but contributed to habitat loss and degradation. Another wave of extinctions followed the introduction—mostly deliberate—of non-native carnivores (snails and worms), directly preying on endemic snails that had evolved in the absence of such predators. The most infamous of these failed ‘biological control’ plans was the introduction of neotropical predatory snails, Euglandina spp., to the high islands of the remote Pacific to control the giant African snail pest, Lissachatina fulica, resulting in the extermination of several tens—and probably hundreds—of narrow-range endemic land snail species. Ornamental use of shells and hobbyist shell collecting may have impacted populations of larger, more colourful species. By contrast, climate change has not been documented as having caused any land snail extinctions. Few land snails are charismatic animals and, in view of the broad and deep impact of aliens on devastated natural habitats, in situ conservation of endemic island snails appears to be possible in only rare cases. There are, however, limited initiatives for ex situ conservation that can buy time and offer a glimmer of hope for positive thinking. Concerted and targeted field work to find and collect representative specimens of remaining species is needed in order that knowledge of the existence of these diverse faunas be available to posterity.